DISCLAIMER: Elwha Legacy Forest Coalition is not affiliated with the Olympic Forest Defenders and did not organize the treesit. The views expressed here reflect the opinion of the author.

Guest Post by Annie Hartnett.

“Tree sitting is a last resort. When you see someone in a tree trying to protect it, you know that every level of our society has failed.”

-Julia Butterfly Hill

They gathered at the locked gate of a logging road outside Port Angeles, Washington. While most were local, some had traveled from as far away as Seattle and Olympia. They wore hiking gear, backpacks, flannels and fleeces, puffy jackets, concert t-shirts, jeans, and beanies in muted colors. Many wore either masks or bandanas to cover their features. Facing off against them on the other side of the locked gate stood three DNR police officers, stances wide, their vehicles lined up behind. They warned the group that anyone who breached their police line would be arrested for trespassing. After a brief standoff and despite the warning, protestors began to filter over, under, and around the gate. They were intent on ascending the logging road to where a group calling themselves the Olympic Forest Defenders had erected a barricade to prevent logging crews from clear-cutting the roughly 85 acres of older growth forest beyond. Attached to the barricade was a platform mounted 80 to 100 feet (or 8 to 10 stories) up a towering Grand Fir, and upon the platform sat a 25-year-old named Fable.

Photo credit: @sacredactionnorthwest

Fable’s 4’ x 8’ platform is attached by a pulley system to a barricade that blocks access to three units of the “Parched” timber sale. If the barricade is removed, the platform will crash to the ground, killing Fable. It is a strange and precarious feat of endurance and idealism undertaken by a young person who is sometimes referred to as “Steve Upthetree,” a play on the name of Washington’s Commissioner of Public Lands, Dave Upthegrove, who has so far refused to cancel the “Parched” timber sale despite appeals from members of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, the city of Port Angeles, and various environmental groups. And it is to Upthegrove and the Washington Department of Natural Resources more generally that Fable and the Olympic Forest Defenders have issued three demands:

- immediate cancellation of the “Parched” Timber Sale,

- a pause on all logging in the Elwha watershed, and

- a permanent ban on logging the remaining mature forests in Western Washington.

History

Tree-sitting as a form of civil disobedience to stop logging, mountain top removal, and the construction of oil pipelines has a relatively short history. The first documented treesit took place in New Zealand in 1978 and was intended to stop logging of the Pureora Forest, home to sacred totara trees and rare kōkako birds. In this first sit, activists lived in the tree canopy for about a week, succeeding in halting the logging of the forest. Subsequently, old growth forest protectors in the Pacific Northwest adopted and expanded the tactic by building platforms and setting up permanent encampments in the tree canopy, gambling that loggers and authorities would not intentionally harm them. Tree-sitting did not become widely known, however, until 1997 when Julia Butterfly Hill, age 23, climbed a thousand-year-old Redwood in California, where she lived for 738 days despite being tossed by fierce windstorms, harassed by loggers, and chilled by the coldest winter in California’s history. The story gained international media attention, and the tree that Hill mounted her protest in, known as Luna, was spared. Not all treesits have been so successful. Many sitters have been arrested and charged, and three have fallen to their deaths.

In some circles, treesitters and their supporters are considered misguided, radical, and even dangerous. In others, the level of commitment, risk, and sacrifice involved bestows on the sitter the mystique of a modern-day saint. In fact, when I saw Fable’s platform, I thought immediately of St. Simeon the Stylite and of other figures from mythology and folk tales.

Photo by Forest2Sea Photography

Mythology and Folklore

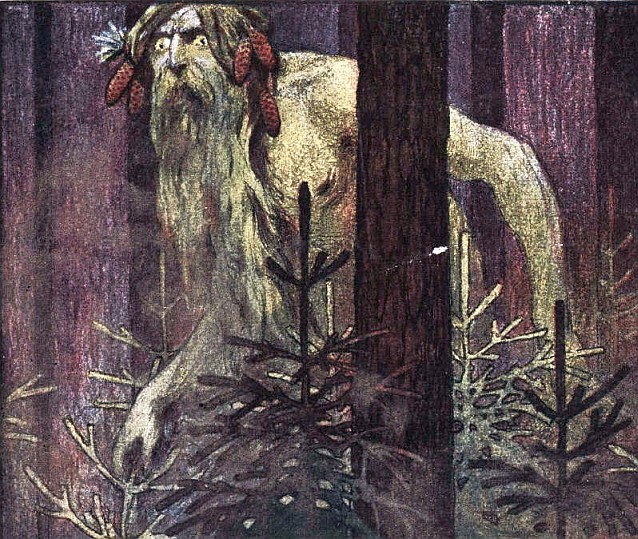

Treesits are a compelling form of civil disobedience because they are archetypal. The forest setting itself is the stuff of fairy tales—think Little Red Riding Hood. In fact, the forest is one of the most common fairy and folk tale settings, a wild and mysterious place where both danger and transformation await. In Western Washington where the treesit is located, indigenous people of speak of se’sxac, commonly known as Sasquatch, a large human-like creature believed to frequent remote forests. In Greek mythology, dryads were nature spirits who lived in trees and often took the form of a beautiful young woman. In Japan, tree spirits called Kodama are said to live in old trees in the deep forest. Kodama bless and steward the land, their life force bound together with the life of the trees they inhabit. If a Kodama dies, its host tree cannot survive and vice versa. In Japanese folklore, cutting down an ancient tree is a sin that calls down a powerful curse on the entire community. Likewise, Slavic mythology tells stories of a forest spirit named Leshy, a shape-shifter and trickster who protects and defends the forest. And Fable, too, is suitably archetypal, identifiable as either the Outlaw, a rebel bent on revolutionary change, or potentially the Hero, someone who makes a journey, faces trials, and achieves a goal or returns with a boon.

Image Credit: By Н. Н. Брут, Magazine «Leshy», Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15825323

Pilgrimage

Here in the United States where Christianity predominates, treesits recall sacrifices made by hermits, saints, and mystics like St. Simeon. A devout follower of Jesus, St. Simeon was a Syrian Christian hermit who practiced his faith by living atop high pillars. Having been kicked out of a monastery due to his extreme asceticism, Simeon lived on his last and final 50-foot pillar home for 37 years. Despite the fact that Simeon made every effort to avoid people, pilgrims sought him out for prayer, healing, and spiritual advice, bringing offerings of food and other necessities to the hermit. Compare this to the groups of supporters making pilgrimages to the treesit. Mostly young, they carry backpacks stuffed with supplies and signs that announce their ideology: Defend the Elwha Forest, Protect Elwha Watershed, Rage for the Forest, Upthegrove Don’t Cut the Grove, We Are All One. They gather at the logging road gate to pray, sing songs, and chant, and then some undertake the 3-4 mile hike up around 1,000 feet of elevation to approach the sitter. Once there, they wave and shout encouragement. Some stay to camp, ensuring support is always available should the sitter need assistance. Donations to the effort have included over 20K in cash; dried beans; gallon jugs of water; braids of sweetgrass; zines and books; homemade soup, bone broth, and bread; solar powered batteries and lanterns; fresh fruits and vegetables; and art supplies.

Purpose

Why go to all this trouble? Why risk arrest and, in the case of the sitter, death? I believe it is because the treesit offers a focal point for processing and potentially assuaging the guilt and anxiety many people feel about the climate crisis, as well as the opportunity to be a part of something larger and of existential significance. Forests capture large amounts of carbon–especially rainforests, which are routinely referred to as “the lungs of the planet.” The forests in Clallam County where the treesit is taking place, are classified as temperate rainforests. Of these rainforests, the legacy (naturally-regrown and biodiverse older forests) sequester significantly more carbon than plantation forests and more effectively reduce the risk of wildfire and soil erosion. Due to the very real threat of climate collapse and mass extinction, the effort to save one forest ultimately becomes an effort to save all forests—one at a time—and in turn to save humanity and all the other species with whom we share this planet.

Thus, the effort to save the “Parched” timber sale feeds into the battle for a livable planet being waged across the world from the temperate rainforests here in the Pacific Northwest to the Amazon to the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada. And as the Bible and myths and folktales from around the world demonstrate, human efforts to understand the world and find meaning and purpose are best conveyed through story. Like most myths and folktales, Fable’s story is a salvation story. What will the moral be? Although we don’t yet know how the story will end, it is clear that Fable and the Olympic Forest Defenders hope for a better future and are taking bold action to ensure it. At a time when so many are gripped by despair or have sunk into apathy, that is something to celebrate.

“To me, the grounds for hope are simply that we don’t know what will happen next, and that the unlikely and the unimaginable transpire quite regularly. And that the unofficial history of the world shows that dedicated individuals and popular movements can shape history and have, though how and when we might win and how long it takes is not predictable.”

― Rebecca Solnit

Photo credit: @sacredactionnorthwest

To learn more or to donate to the Olympic Forest Defenders, go to this link: https://linktr.ee/olympicforestdefenders

SOURCES:

https://www.bfro.net/legends/salish.htm

https://elwhalegacyforests.org/parched/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tree_sitting

https://acoel.org/an-unexpected-journey-can-tree-sitting-drive-policy/

https://www.patagonia.com/stories/why-we-sit-in-trees/story-90685.html

https://yokai.com/kodama/?srsltid=AfmBOopJW0IZis4vgJOVtqkJZdOiSBWcG9nAlhCK7s_D8ohOcej2Chct

https://hyakumonogatari.com/2012/08/05/kodama-the-tree-spirit/